HOSPITAL ACCESS MANAGEMENT MUST ALSO BE APPLIED TO INNER SPACE

As posted on LinkedIn Pulse on September 14, 2017

Access management may begin at the perimeter, but it should not end there. This is particularly true for hospitals. Most hospitals generally have two primary points of public ingress: The Emergency Department and the Main Lobby. However, most hospitals, hotels and other public buildings, have numerous unofficial points of entry, such as fire doors, loading docks and facility management areas. Pertaining to most hospitals, it usually is not difficult to overcome limited access portals. Given the variety recent of Workplace Violence episodes, it is clear that access management must also be applied internally.

In fact, during the course of providing security assessments, we have discovered that it is not infrequent to find egress-only doors, propped open (often by smokers).

Even when there are visitor control procedures in place, they are often not difficult to compromise. However, there are many hospital visitor control systems that do a reasonably good job of ingress control, when properly applied and supported by security interaction. Brands such as STOPware and their PassagePoint software utilize a driver’s license swipe system that can be a reasonably effective deterrent to most surreptitious entry. The mere act of scanning driver’s licenses may be a deterrent to surreptitious entry.

Albeit, these systems are helpful, but they cannot replace the human involvement and the judgment of staff, bolstered by application security awareness training. However, it is not uncommon that some visitor access systems are perceived to be a panacea that will ensure the security integrity of the hospital. As a practical matter, visitor management systems are merely a tool and a single first step of a comprehensive access management strategy.

This means that access management (visitor control) does not end at the perimeter. There must also be internal access control programs aimed at reasonably protecting inner space. For example, patients who are under a protective order, will require special consideration. The mere assignment of an alias to a patient under a protective order, does not allow the hospital to let its collective guard down. In fact, there have been numerous lawsuits centered of the issue of the efficacy of adequate protection, including access management protocols. With any access management system/protocol, trust, but verify.

If more convincing is required in support of this thesis, simply search the internet for a wide range of hospital assaults. These assaults include, but are not limited to, sexual assaults, assault and battery, as well as active shooter episodes, all occurring within an alleged secure perimeter. You will find that many of the active shooter incursions over the past two years, have occurred well beyond the building’s outer perimeter. There is no substitute for staff awareness and participation.

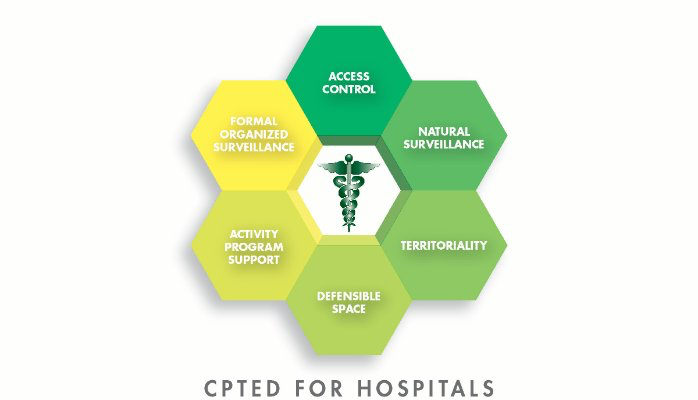

Effective security programs may begin at the perimeter, but by no means should they end at the perimeter. The same admonition is applicable to CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design). (For those who are not are not conversant with CPTED principals, you may want to want to read 21st Century Security & CPTED.) CPTED is cost efficient strategy that will address the fundamentals of any effective security program. CPTED is particularly appropriate for hospitals.

The graphic above depicts some of the access control security components that may be supported by CPTED.

Security professionals who understand the application of CPTED methodologies will become a much more effective force for good. Employees who understand the principals of natural surveillance, will become effective security surrogates. The bottom-line, if your security program is perceived as ineffective, more likely than not, perception will prevail.

By way of example: One of the implicit goals of CPTED design is to support wayfinding in public buildings. including hospitals. Wayfinding commonly supported by kiosks, indoor maps, directional visual clues and building directories. There have been entire books written on the topic of wayfinding. Some hospital use floor markings to get a visitor from point A to point B. Spaces that include areas outside the normal vocabulary of visitors. show the need for a common set of language-independent symbols to either encourage or discourage non-employee access to areas within the building, including hospitals. Penetration can be either encouraged or discouraged. Even stanchions with theater rope may be used to discourage access, when backed up by employee vigilance. Not all access control needs to be electro-mechanical. Wayfinding can also dissuade access to restricted areas within the hospital property. Therefore, what is the antithesis of wayfinding when we want to restrict access?

Clearly special areas, such as Labor and Delivery, pediatrics, behavioral health and battered women treatment facilities, require more traditional target hardening. These methodologies auger for a more defined territorial definition of defensible space. Video surveillance systems provide another option when defining and controlling defensible space.

If further information regarding CPTED, we would be happy to respond to any inquiries.

CPTED methodologies work best, when security and loss prevention programs are a team effort reinforced by the articulation of security awareness, and the training thereof.

William H. Nesbitt, CPP; Certified CPTED Practitioner; President SMSI Inc.

Contact: 805-499-3800; E-Mail: bill@smsiinc.com; Website: www.smsiinc.com